The economic ripple effects of the 2025 fertilizer subsidy program are beginning to manifest in Kenya’s national food security metrics with startling clarity. According to the June 2025 Treasury budget highlights, the government has allocated Ksh 8 billion specifically for the Fertilizer Subsidy Programme for the 2025/2026 financial year. This is part of a broader Ksh 47.6 billion agricultural transformation budget aimed at moving Kenya from a “food deficit” nation to a “food surplus” economy. By slashing the cost of a 50kg bag by approximately 60% compared to market rates, the program has successfully triggered a 38.9% increase in maize production in high-potential regions, directly contributing to the stabilization of mealie-meal prices in urban centers like Nakuru and Nairobi.

However, the 2025 policy is no longer just about quantity; it is increasingly about soil health and long-term sustainability. New directives from the Ministry of Agriculture emphasize the use of NPK 23:23:0 and other non-acidic blends to correct soil degradation caused by years of over-relying on DAP. This scientific approach ensures that the “bumper harvests” seen this year are not a one-time fluke but the beginning of a sustained increase in yield per hectare. For the Kenyan farmer, this shift represents a move toward “Precision Agriculture,” where the digital data collected during KIAMIS registration helps the government determine which specific nutrient blends are needed for which regions, potentially saving billions in wasted inputs.

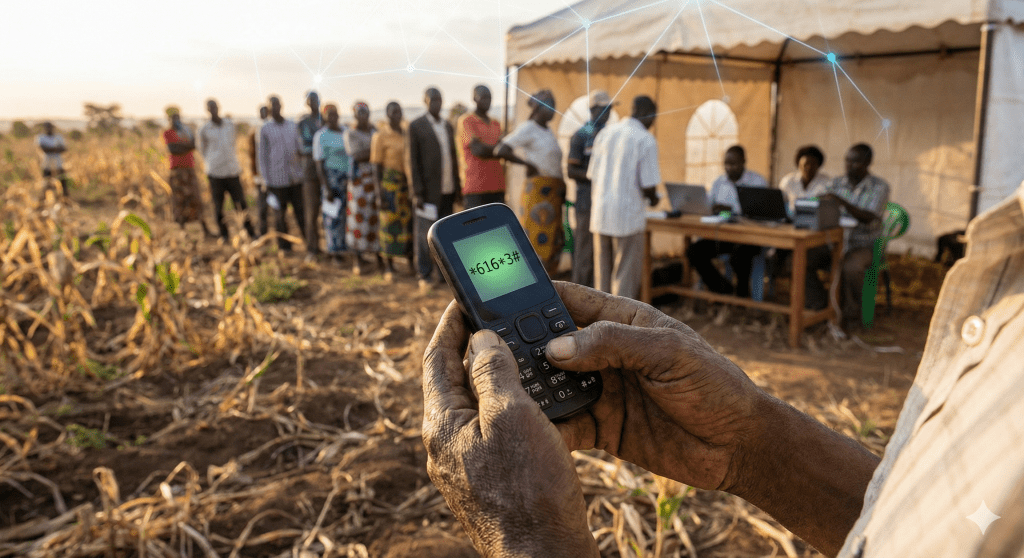

The final piece of this economic puzzle lies in the integration of “De-Risking” strategies. For the first time, the 2025 digital registration automatically links farmers to climate-risk insurance and credit facilities. This means that a farmer who buys subsidized fertilizer is also protected against the devastating losses of drought or floods, making the entire agricultural sector more attractive to young “agri-preneurs.” As Jijuze continues to monitor these developments, it is clear that the fertilizer subsidy is the anchor of a much larger economic engine. By empowering smallholders with affordable inputs and digital tools, Kenya is slowly rebuilding its agricultural backbone, turning the “kabambe” phone into a powerful tool for national prosperity.

References:

Capital Business Maize harvest to hit 70mn bags in 2025, up from 67mn last year

The Kenyan Wall Street The Hidden Costs of Kenya’s Fertiliser Subsidy Model

Jijuze How to Access Subsidized Fertilizer in Kenya