The final frontier of the malaria fight is as much about economics and topography as it is about biology. As temperatures rise, malaria is climbing into highland areas where populations lack natural immunity . Research shows that “U-shaped” valleys in these regions are five times more likely to host parasites than steeper “V-shaped” valleys, as their flat floors provide stagnant water for vector breeding.

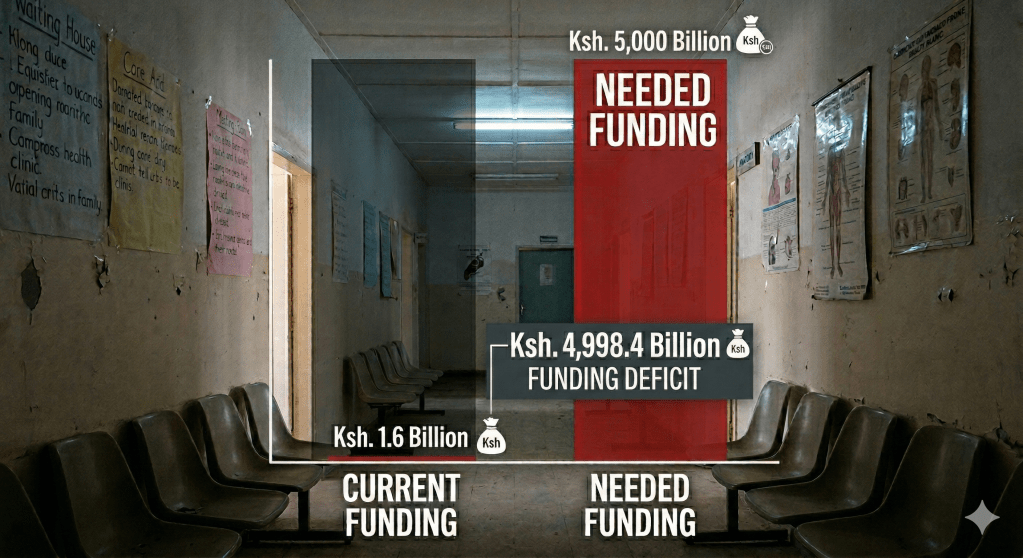

While Kenya’s 2023-2027 strategy aims for a 90% reduction in deaths, these goals are currently balanced on the edge of a financial abyss . In 2024, global malaria funding reached only $3.9 billion—less than half of what is needed annually. Abrupt 2025 US funding cuts have triggered a “cascading collapse” in health infrastructure, with nearly 25,000 community health workers in Kenya facing imminent layoffs .

Without sustainable, government-led financing models, the health system remains vulnerable to unplanned disruptions. To secure a malaria-free future, Kenya must pivot toward local manufacturing of diagnostics and vaccines while integrating climate data into every level of health governance. The line between a breathtaking view of elimination and a dangerous resurgence is currently dependent on filling these “ghost deficits” in aid.

References:

Human Rights Watch Donor Nation Cuts to Global Health Financing Affect Millions

Physicians for Human Rights “The System is Folding in on Itself”: The Impact of U.S. Global Health Funding Cuts in Kenya