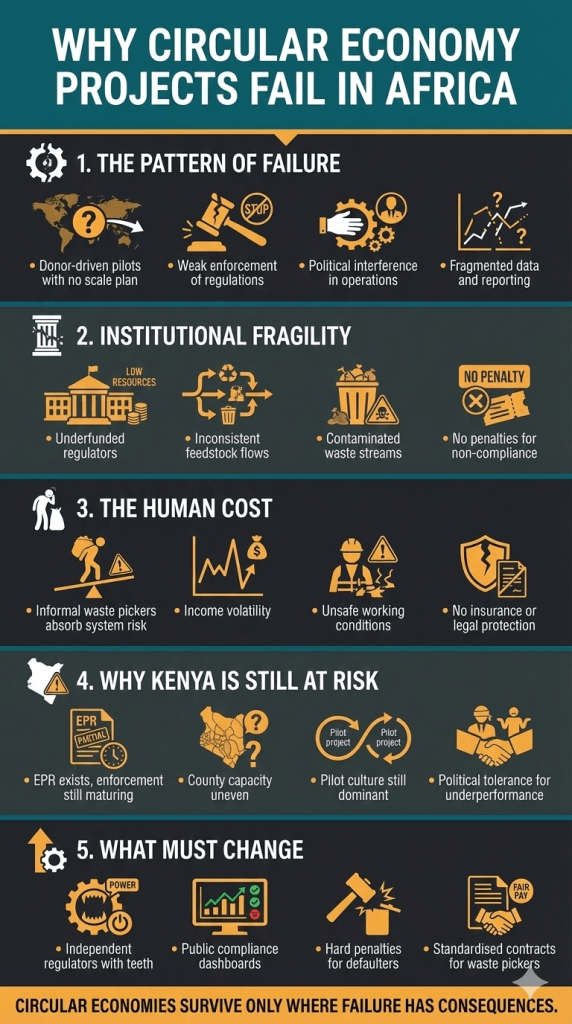

Africa’s circular economy graveyard is already full — littered with donor-funded pilots, ribbon-cut recycling plants, and policy frameworks that never made it past the launch event. The continent does not lack ideas, technologies, or goodwill. It lacks execution discipline. Circular projects fail not because the science is flawed, but because governance is weak, incentives are misaligned, and accountability dissolves the moment external funding expires. Kenya is not immune. Despite progress on EPR, private-sector engagement, and innovation, the country remains structurally exposed to the same failure patterns that have derailed circular initiatives across the continent: regulatory softness, political interference, underpriced waste, unreliable data, and a dangerous tolerance for “pilot culture” that rewards announcements more than outcomes.

The most common failure point is institutional fragility. Waste systems collapse when counties are underfunded, when regulators lack enforcement capacity, and when standards exist on paper but not in practice. Facilities designed to process thousands of tonnes operate at a fraction of capacity because feedstock flows are unstable, contaminated, or diverted through informal channels. Producers default to virgin materials because enforcement is weak. Investors retreat because market signals shift without warning. And in the background, the informal waste workforce absorbs the shock — losing income, facing unsafe conditions, and subsidizing system failure with their bodies. This is the brutal reality: without strong institutions, circularity becomes extractive, not regenerative.

Kenya now stands at a narrow threshold between replication and rupture. It can repeat the familiar African cycle — ambitious strategies undermined by weak enforcement and politicized implementation — or it can confront the uncomfortable truth that circular economies only work when failure is punished and compliance is unavoidable. That means independent regulators with teeth, public dashboards that expose non-compliance, hard penalties for EPR defaulters, standardized contracts that protect waste pickers, and zero tolerance for underperforming infrastructure. There are no shortcuts left. As the global plastics transition accelerates, Kenya will either prove it can govern complexity — or it will join the long list of countries that mistook intention for capacity. This is the moment where rhetoric must end, and consequences must begin.

References:

OECD Extended producer responsibility and economic instruments

GreenPeace New documentary exposes recycling fallacy and health impacts of plastic pollution on Kenya’s waste workers

MarcoPolis Silafrica Kenya’s Akshay Shah on Sustainable Packaging and the Future of the Circular Economy in Africa

The Exchange Africa Africa’s SMEs: How Policymakers Can Speed Up Growth and Innovation

Frontiers in Sustainability Transitioning circular economy from policy to practice in Kenya

The Standard Counties blamed for failure to adopt waste management plants

Envaco The Role of Circular Economy in Kenya’s Waste Management Future

EnvyNature Waste Management in Africa: What’s Working and What’s Next