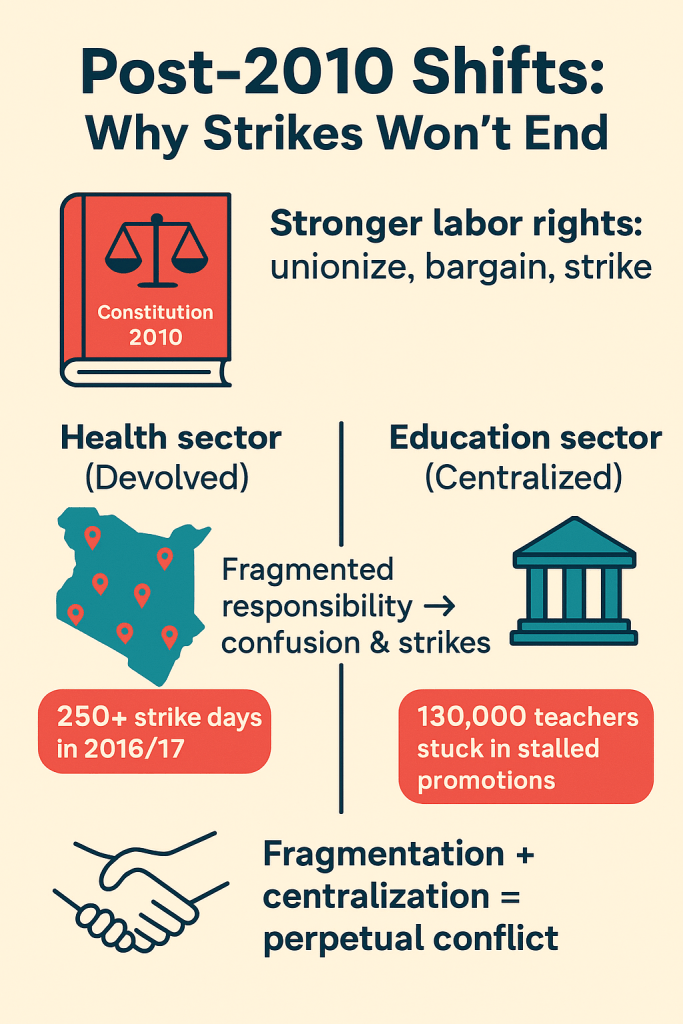

Kenya’s labor unrest cannot be fully explained by the Kenya Kwanza administration’s missteps alone. The deeper roots of today’s incessant strikes lie in structural shifts unleashed by the 2010 Constitution. By embedding strong labor rights—including the freedom to unionize, collectively bargain, and strike—while simultaneously devolving key government functions, the Constitution created both an empowered workforce and a fragmented system of accountability. These changes reshaped labor relations across education and health, planting the seeds for recurrent clashes between workers, unions, and the state.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the health sector. When the 2010 Constitution devolved primary and secondary health services to 47 county governments, it fractured the once-unified employer-employee relationship between health unions and the state. Doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals suddenly faced a dual negotiation front: the national Ministry of Health and individual county governors. This decentralization introduced ambiguity about who should fund or enforce collective bargaining agreements (CBAs), fueling a wave of prolonged nationwide strikes. The infamous 2016–2017 standoff—where doctors and nurses collectively downed tools for nearly a year, resulting in 250 lost strike days—exemplified how devolution multiplied points of conflict rather than streamlining accountability.

By contrast, the education sector retained a centralized structure under the Teachers Service Commission (TSC). While this avoided the maze of devolved negotiations, it meant that disputes often escalated into high-stakes, nationwide confrontations. Teachers’ unions, dealing with a single employer, have consistently locked horns with the TSC over promotions, career progression, and salary schemes. Despite this centralization, the state has still failed to fund signed CBAs adequately, proving that the conflict is not just about institutional design but also about political will. Ultimately, the post-2010 constitutional settlement entrenched a dual dilemma: fragmentation in devolved sectors like health, and high-stakes concentration in centralized sectors like education—both of which ensure that labor unrest remains baked into Kenya’s governance model.

References:

KMPDU Promise Made, Promise Kept As Doctors Receive Full 2017–2024 CBA Arrears

BMJ Global Health Tackling health professionals’ strikes: an essential part of health system strengthening in Kenya

Health Business Ministry of Health signs agreement with KMPDU in new deal

Finn Partners The Evolution of Healthcare in Kenya Amidst Doctor’s Strike and the Rise of Digital Health Innovations