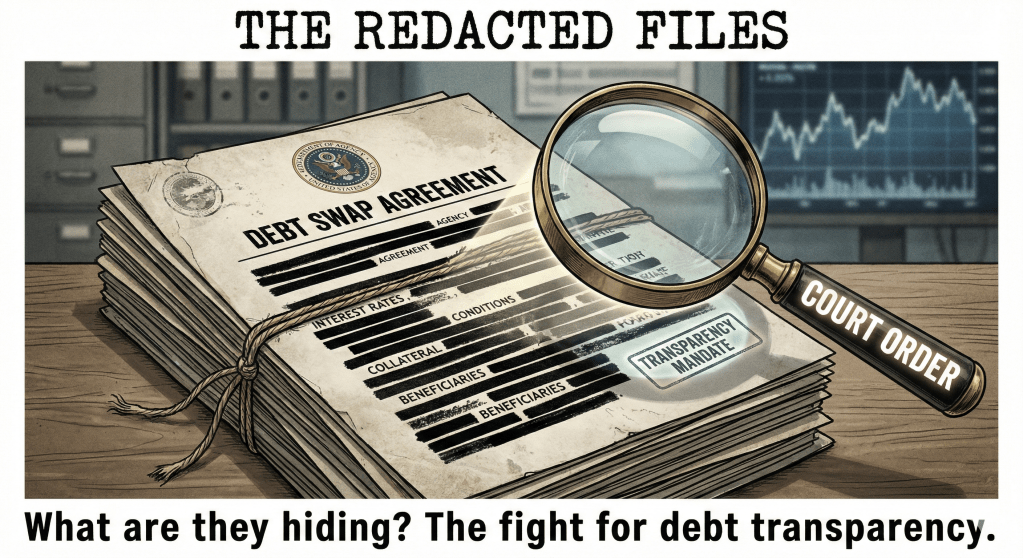

Despite the high stakes, the specific terms of the debt-for-food swap remain shrouded in secrecy, sparking legal battles and civil society alarm. A case filed at the East African Court of Justice, Wanjiru Gikonyo v The Attorney General, challenges the government’s refusal to disclose the full details of sovereign debt agreements. Litigants argue that committing future tax revenues and “savings” to long-term projects without public participation is unconstitutional. The lack of a public dashboard detailing exactly how the Sh129 billion will be spent creates a “transparency deficit” that invites mismanagement.

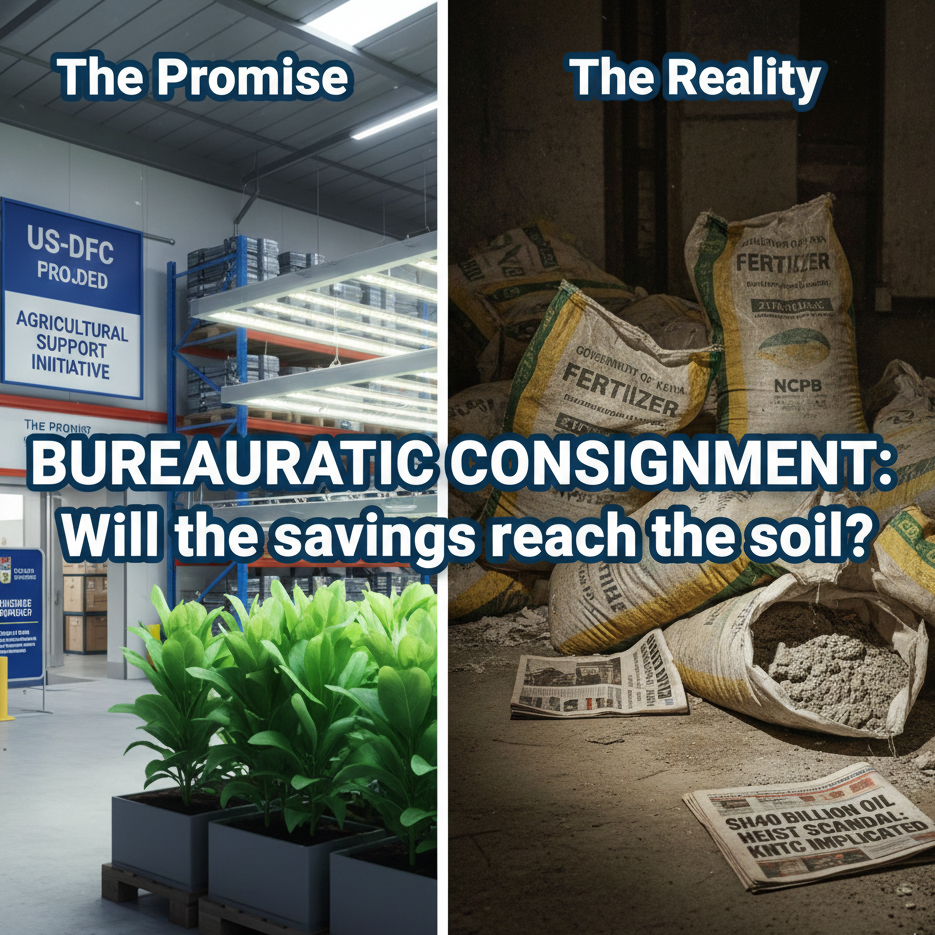

This opacity exacerbates the “sovereignty paradox.” By allowing the US-DFC and WFP to dictate the terms of expenditure, Kenya is effectively admitting that its own institutions cannot be trusted. While external conditionality acts as a safeguard against local corruption, the public remains in the dark about what exactly has been signed away. Are there hidden fees? What are the penalties for non-compliance? Without full disclosure, the Kenyan taxpayer is a passenger in a vehicle being driven by foreign creditors.

Transparency is not just a legal formality; it is the only disinfectant strong enough to prevent the “bureaucratic consignment” of funds. Civil society is demanding that the Treasury publish every shilling of the “savings” and every project beneficiary. Until then, the debt swap remains a “black box”—a deal negotiated in boardrooms in Washington and Nairobi, with the bill sent to the citizen who has no say in the menu.

References:

Afronomics Law Sovereign Debt News Update No. 147: The Promises and Transparency Pitfalls of Kenya’s $1 Billion Debt-for-Food Swap

The Institute for Social Accountability The High Court has ordered the National Treasury to disclose critical information on Kenya’s bilateral loans and sovereign bonds.