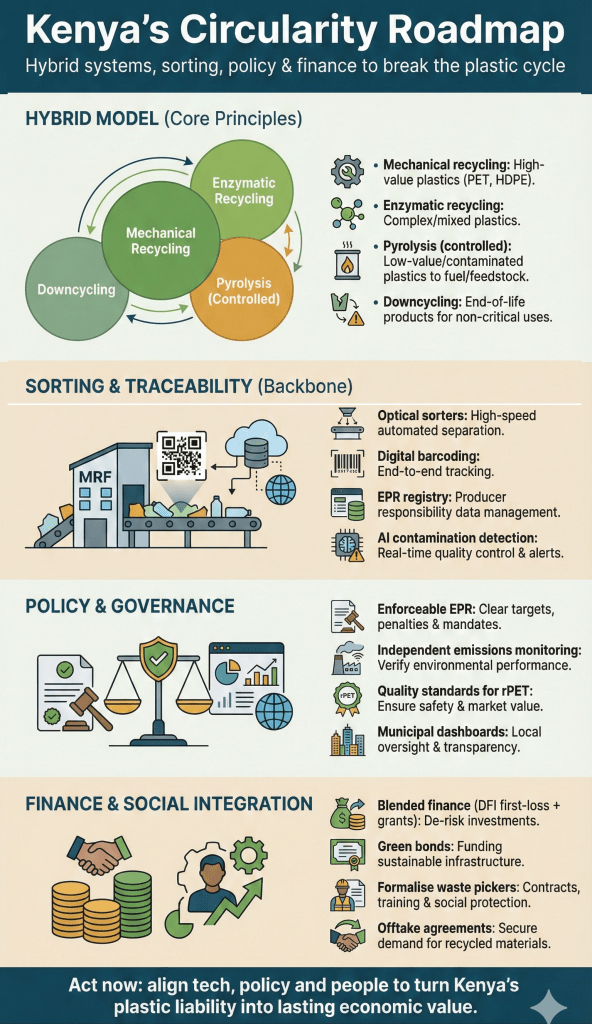

Kenya’s plastic crisis will not be solved by a single breakthrough, a single technology, or a single policy decree. If the past four posts have made anything clear, it is that this challenge is multi-layered — social, economic, technological, institutional — and requires a system far more sophisticated than anything the country has attempted so far. Mechanical recycling alone cannot handle the volume or complexity of the waste stream. Enzymatic recycling promises high-value transformation but depends on disciplined feedstock management and purposeful capital. Pyrolysis offers a pathway for Kenya’s dirtiest plastics, but only if environmental oversight becomes a non-negotiable pillar of implementation. And behind all of it stands the human backbone of Kenya’s recycling economy: the informal waste pickers whose labour determines whether any of these systems succeed or fail. The future Kenya wants — clean cities, competitive green industries, dignified work, and reduced dependence on virgin petrochemicals — will require a hybrid circularity model capable of integrating all these components without allowing any one of them to cannibalize the rest.

At the center of this roadmap is a quiet revolution in sorting and digital traceability — the infrastructure Kenya has never fully built. Without accurate sorting, mechanical recycling loses efficiency, enzymatic systems lose purity, and pyrolysis loses economic viability. High-tech optical sorters, digital barcoding, blockchain-driven EPR registries, and AI-enabled materials classification systems are no longer luxuries; they are foundational to a modern circular economy. Countries that have mastered these — from South Korea to France — have done so by centralizing oversight, enforcing producer responsibility, and investing heavily in data-first waste systems. Kenya’s EPR regulations are a promising start, but they require real teeth: mandatory reporting, enforceable purchase obligations for recycled content, non-negotiable penalties for non-compliance, and transparent digital dashboards accessible to the public. Anything less risks turning EPR into another policy with impressive language but weak outcomes.

What Kenya builds over the next five years will determine whether the nation becomes a continental leader in green industrialization or remains trapped in a costly cycle of environmental degradation and lost economic opportunity. The roadmap is clear:

• Mechanical recycling must continue as the backbone for high-volume, easily recoverable plastics.

• Enzymatic recycling should anchor Kenya’s entry into premium circular markets — producing high-grade rPET for export and high-value manufacturing.

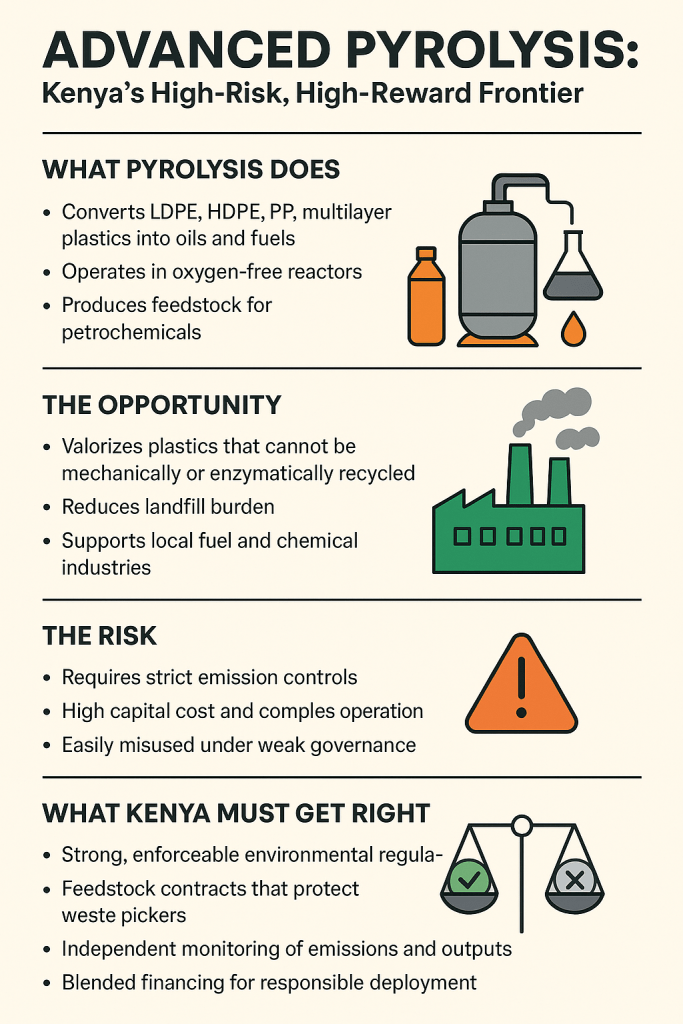

• Advanced pyrolysis should be deployed cautiously, strategically, and only under strict regulatory regimes to handle non-recyclable residues.

• Waste pickers must be formalized, protected, and integrated into digital systems that guarantee stable income, health protections, and training.

• Municipalities must build modern MRFs, supervised by independent bodies with zero political interference.

• Financing must be blended — public, private, philanthropic — to derisk innovation and scale responsibly.

If Kenya commits to these pillars, it can escape the linear waste economy and construct a circular system that is clean, fair, profitable, and future-ready.

If it fails, the country will remain stuck in a loop where every new solution dies under the weight of the same old structural weaknesses.

References:

Kenya Plastics Pact Kenya Plastics Pact & WWF-Kenya Drive Plastic Recycling Efforts Amid EPR Implementation

The Star Tackling pollution: How Murang’a engineer is converting plastic waste into clean fuel

Africa News Nairobi-based Company Turns Plastic Waste into Eco-Friendly Bricks

Kenya News Agency Converting Plastic Waste into Building Materials

The National Council for Law Reporting The Sustainable Waste Management (Extended Producer Responsibility) Regulations

Kenya Plastics Pact Kenya Plastics Pact Commits to Combat Plastic Pollution and Support the Implementation of Extended Producer Responsibility in Kenya