After dissecting Kenya’s plastic paradox, amplifying the struggle of waste pickers, and spotlighting the promise of enzymatic recycling, we now turn to one of the most contested technologies in the global waste-to-value conversation: Advanced Pyrolysis. This is the method frequently hailed as the “missing link” for non-recyclable plastics — yet equally criticized for being expensive, energy-hungry, and easily corrupted by weak regulation. And for a country like Kenya, staring at overflowing dumpsites and facing rising global pressure to meet circularity targets, pyrolysis represents both a thrilling opportunity and a dangerous temptation.

The stakes here are far more complex than in enzymatic or mechanical recycling, because pyrolysis operates at the intersection of energy policy, industrial chemistry, geopolitics, and climate governance — a mix Kenya has historically struggled to reconcile coherently.

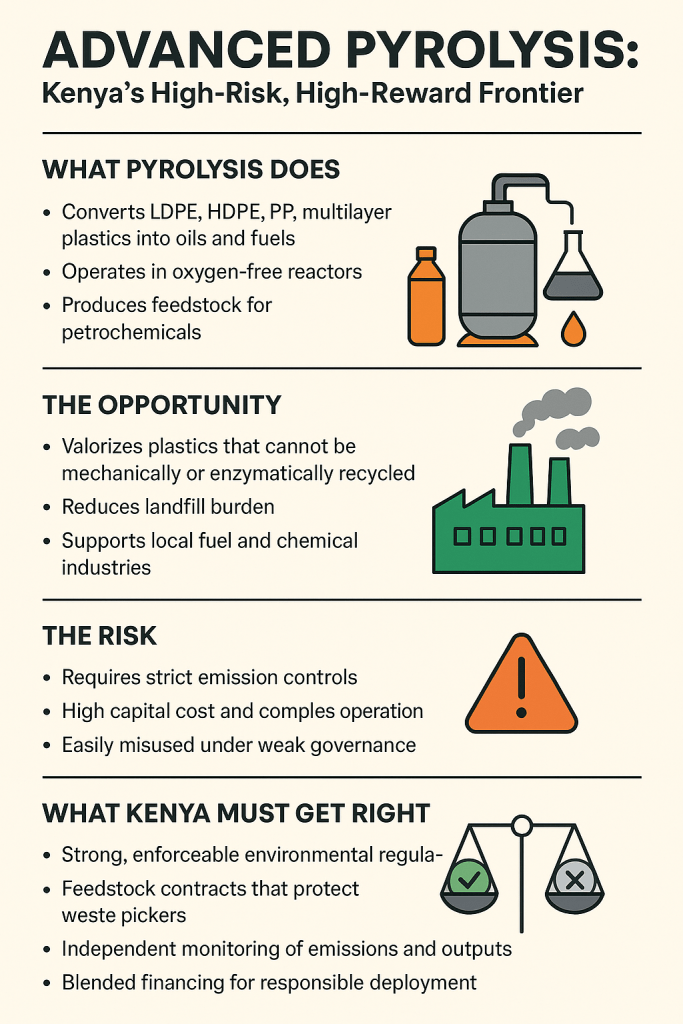

At its core, advanced pyrolysis breaks down hard-to-recycle plastics — LDPE, HDPE, PP, multi-layer laminates — by heating them in oxygen-free reactors, converting them into fuels, naphtha, waxes, or feedstock oils that can re-enter petrochemical production. In theory, this allows Kenya to tap into the vast volumes of low-value plastic that currently have no market and end up burned, buried, or blown into rivers. It offers a potential pathway to energy diversification at a time when fuel costs continue to shake households and industries. And it carries significant economic upside if Kenya positions itself as a regional hub for circular petrochemicals in East Africa.

But the discipline required to execute pyrolysis safely, profitably, and sustainably is far greater than what Kenya’s current plastic waste governance demonstrates. The technology demands consistent feedstock, stable power, advanced emission control systems, certified output testing, and rigorous oversight — factors that have caused even advanced economies to sabotage their own pyrolysis pilots when shortcuts were taken.

This is why pyrolysis is both a strategic advantage and a national vulnerability. If Kenya rushes into pyrolysis without robust environmental regulation, credible emissions monitoring, and a clear economic model that avoids underpricing waste picker feedstock, the country risks creating a new version of the same inequities we are trying to solve — except now, with industrial smokestacks attached. Yet if Kenya gets the sequencing right — establishing strict standards, blending public financing with private risk capital, creating transparent PET/PO feedstock corridors, and placing waste pickers at the center of value creation — pyrolysis could complement enzymatic recycling and cement Kenya’s position as a regional circular economy powerhouse.

The question, then, is not whether pyrolysis works. The question is whether Kenya can adopt it responsibly — without repeating the extractive, opaque, poorly regulated industrial patterns that have crippled other sectors before.

Because the truth is simple: pyrolysis is not a shortcut. It is a stress test of Kenya’s capacity to govern the future.

References:

The Star Tackling pollution: How Murang’a engineer is converting plastic waste into clean fuel

Kenya News Agency Engineer develops certified diesel from plastic waste

The Star Ambitious Murang’a man invents trailblazing fuel blends from plastic waste

Business Daily ICDC invests Sh420m in firm that converts plastic waste into energy

The Guardian Shell quietly backs away from pledge to increase ‘advanced recycling’ of plastics

Borderless Pyrolysis under fire: Environmental and health concerns cast doubt on “miracle” technology

Africa News The Kenyan entrepreneur turning plastic to fuel