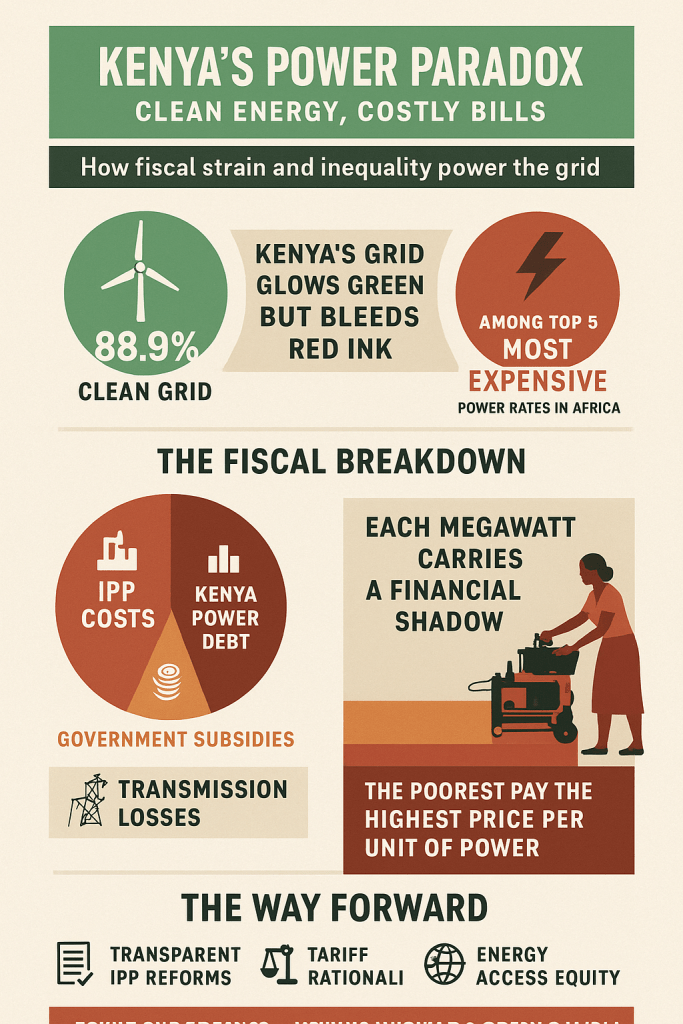

Kenya’s power paradox runs deep: a country rich in renewable generation, yet burdened by some of the highest electricity costs in Africa. On paper, nearly 90% of Kenya’s grid is green — geothermal, hydro, and wind forming a rare climate success story. But for millions of households and industries, that triumph hasn’t translated into affordability. Consumers pay between KSh 25 and 30 per kilowatt-hour, rates that undercut competitiveness and squeeze living standards. In the informal settlements of Nairobi, small shop owners still ration power hours to manage costs, while factories in Athi River and Thika cite electricity tariffs as a primary obstacle to growth. The contradiction is glaring: Kenya has abundant clean power, yet access remains economically exclusionary — an irony that exposes how generation success can mask distributional failure.

At the core of this crisis lies a web of fiscal and contractual distortions. Independent Power Producer (IPP) deals, negotiated during periods of emergency and donor pressure, locked Kenya Power into long-term capacity charges that bleed the utility dry even when consumption dips. The state utility’s balance sheet tells a grim story — mounting arrears, bailout dependencies, and a tariff structure that barely recovers operational costs. Subsidies designed to protect consumers often backfire, distorting market signals and worsening public debt. Populist interventions — from tariff freezes to election-time lifeline promises — have turned energy pricing into political theatre, undermining reform momentum. Meanwhile, Kenya’s push toward big-ticket projects like nuclear power adds new fiscal layers to an already fragile system. It’s a balancing act where every kilowatt carries not just a cost, but a liability.

The human toll of this misalignment is profound. While urban elites and large manufacturers negotiate preferential rates, rural households and informal traders bear the heaviest burden. Many still rely on kerosene lamps and diesel generators — paying more per unit of energy than the grid-connected middle class. The national electrification dream, once buoyed by donor-funded rural projects, has slowed under the weight of poor planning and financial strain. Energy inequality now mirrors broader economic divides, threatening social cohesion and trust in public institutions. The solution lies not in more megawatts, but in smarter management — transparent IPP contracts, realistic tariffs, and equity-centered reform. Kenya’s next decade will determine whether electricity remains a privilege or becomes the universal right it was promised to be. And as the country turns toward nuclear expansion, the cost question will no longer be technical — it will be moral.

References:

Ecofin Agency Kenya Ranks Best in Africa for Power Rules but Prices Keep Rising

Global Petrol Prices Kenya electricity prices

Citizen Digital Cost of electricity: MPs question high amounts paid to independent power producers

The Star Lights on, bills up: Paradox of high electricity costs in Kenya despite abundant renewable sources

Daily Nation Kenya Power MD: Why your electricity bill is so high

Stears Increased electricity tariffs strain Kenyan low and middle-income households

Business Daily Kenyan homes pay highest electricity bills in Eastern, Central Africa

Sadly this is what happens in high penetration of renewables. Its cause by a lack of network stiffness and a network devoid of intrinsic values.

The world has become obsessed with digital reactive grid designs, rather than analog resistive ones. There’s a great article “Why grids must be built on intrinsic” on my blog. You might find it enlightening.

Nice