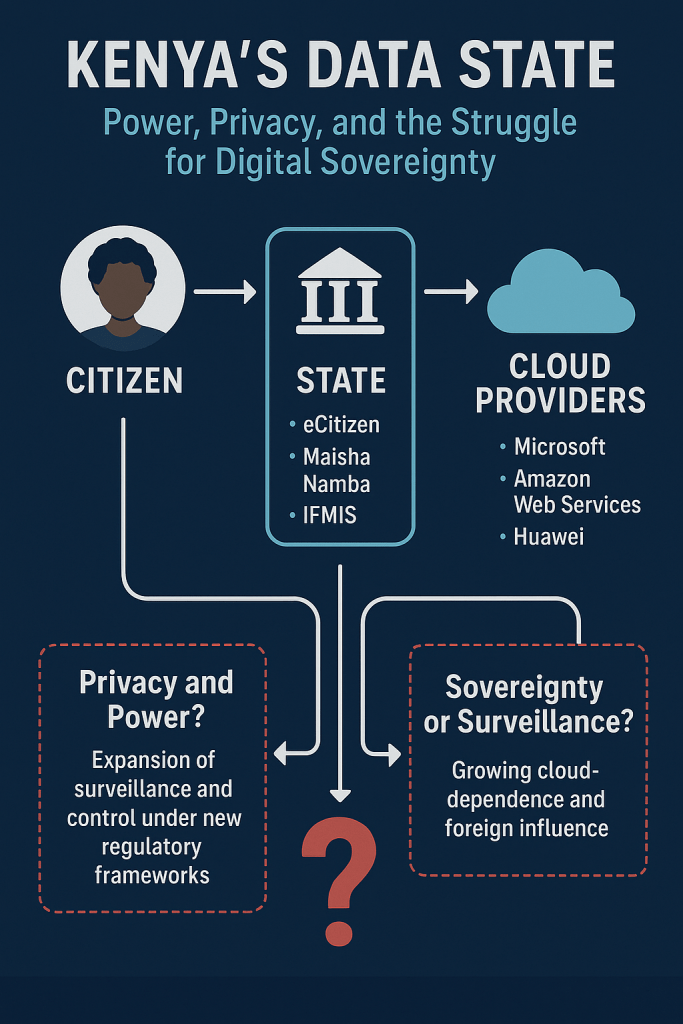

Kenya’s digital transformation has reached an inflection point. Through the integration of platforms such as eCitizen, Maisha Namba, and IFMIS, the State now operates as a vast data processor — collecting, linking, and analyzing the lives of millions of citizens in real time. What began as a quest for efficiency has evolved into a new form of governance: one built on algorithms and infrastructure rather than laws and institutions. Under the Data Protection Act (DPA) 2019, citizens were promised control over their personal information, while the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC) was established as the custodian of privacy rights. Yet in practice, enforcement remains weak, politically constrained, and under-resourced. The result is a paradox: Kenya’s most progressive digital laws coexist with some of its most opaque data practices. As it is, the country is witnessing the emergence of a public-private algorithmic interlock — a hybrid system in which state and corporate power merge to govern through data.

At the core of this interlock lies Kenya’s cloud dependency, the Achilles’ heel of its digital sovereignty. The Cloud-First Policy (2023) was designed to enhance efficiency by migrating state systems to cloud infrastructure. In reality, it has tethered Kenya’s critical data to foreign providers — notably Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services (AWS), and Huawei Cloud. These platforms host sensitive national databases, including immigration, healthcare, and education records. While they offer advanced security and performance, they also place Kenya’s sovereignty at risk: jurisdiction over this data often lies outside national reach. The government’s own National Cloud Data Centre at Konza Technopolis, meant to localize and secure state data, remains underutilized, operating below capacity. Analysts warn that this imbalance represents a “sovereignty paradox” — a situation in which Kenya aspires to digital independence but relies on foreign entities to store and secure the very data that constitutes its national identity. In a world where information is power, Kenya’s cloud partnerships may have outsourced the core infrastructure of governance itself.

This dependency also feeds into the expanding reach of digital surveillance, often justified under the banner of cybersecurity. The fusion of citizen databases — spanning KRA tax systems, telecommunication registries, and biometric IDs — enables predictive profiling that blurs the boundary between public safety and state intrusion. The Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act 2024 further amplifies this concern, granting security agencies powers to intercept and remove online content without prior judicial approval. Civil-society groups warn that such tools could easily be weaponized to silence critics and monitor dissent under the guise of digital policing. At the same time, Kenya still lacks a comprehensive data ownership framework, leaving citizens powerless to reclaim or delete their data. The ODPC’s reactive approach, compounded by political pressure, means violations are often addressed only after they occur. Looking ahead, Kenya’s battle for democracy is increasingly being fought not in parliaments or streets but within servers and code. Whether the nation’s digital transformation strengthens sovereignty or surrenders it will depend on one crucial question — who ultimately controls the data that defines its people.

References:

Tech Africa News Kenya Begins Drafting National Data Governance Policy

Microsoft Microsoft and G42 announce $1 billion comprehensive digital ecosystem initiative for Kenya

Site Selection Africa: Digital Giants Unveil Billion-Dollar Data and Skills Plan for Kenya and East Africa

Data Guidance Kenya: The Cloud Policy – what organizations need to know

CM Advocates Legal Boundaries of Data Commissioner’s Enforcement Powers