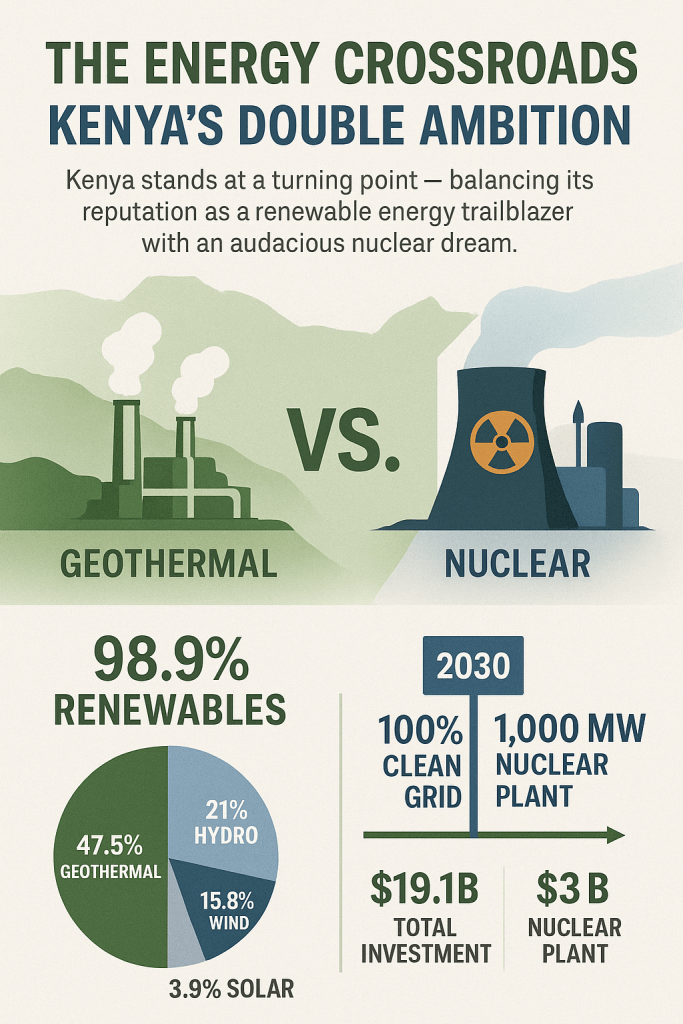

Kenya’s energy story is being rewritten on two dramatically different blueprints. In the steaming Rift Valley, the hum of geothermal turbines tells the story of a nation that has nearly conquered its clean energy dream — with close to 90% of its power drawn from renewables, mainly geothermal, hydro, and wind. This success has made Kenya a continental symbol of green progress and a diplomatic darling of climate-conscious financiers. Yet, in quiet government boardrooms in Nairobi, a second vision gathers force — one powered not by heat from the earth but by the fission of the atom. The Nuclear Power and Energy Agency (NuPEA) is advancing plans for a 1,000-megawatt nuclear plant set to begin construction by 2027 and deliver electricity by 2034. The result is a nation straddling a paradox: can Kenya remain the face of Africa’s green revolution while becoming its first atomic pioneer?

Behind the glossy renewable statistics lies a more fragile truth. Kenya’s hydropower output has fallen prey to erratic weather, with droughts cutting generation by 15% in 2022, while rising demand — now peaking above 2,300 megawatts — has exposed the limits of an overstretched grid. The blackouts that have rippled through homes and factories underscore a growing reality: renewable success has not translated into industrial reliability. For planners pursuing Vision 2030 and the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA), the numbers are sobering — the nation’s installed capacity of 3,400 MW must grow nearly twenty-fold to meet future manufacturing and digital-era needs. In this context, nuclear energy is being framed not as an ideological betrayal of green ideals, but as a pragmatic lifeline — a bid for baseload stability, energy sovereignty, and freedom from the climate vulnerabilities that shadow the country’s renewable crown.

Yet this dual pursuit exposes Kenya to a dangerous collision of timelines, financing, and identity. The government’s promise of a 100% renewable grid by 2030 sits uneasily beside its nuclear timeline, forcing a quiet redefinition of “clean” from renewable to low-carbon. The nuclear build, projected at $2–3 billion, also competes for scarce development funding with the $19.1 billion needed to expand renewables under the National Energy Compact. Beyond cost, the gamble risks eroding Kenya’s most valuable diplomatic asset — its green reputation. As the country steps onto the nuclear stage, it must navigate a delicate balance between sustaining its climate leadership and pursuing industrial power. The question now confronting Nairobi is not just how to keep the lights on, but how to do so without dimming the glow of its hard-won green identity — a tension that will define Kenya’s energy destiny and set the stage for the next chapter: the global power play behind its nuclear dream.

References:

African Business Kenya plans first nuclear plant within decade

Government Advertising Agency Kenya targets 20,000MW nuclear power to ease electricity shortfall

The Kenyan Wall Street Kenya Sets New Electricity Demand Record as Grid Faces Rapid Growth

Business Daily Electricity production hits new record high on rising demand

Kenya News Agency NuPEA pledges nuclear power production takeoff by 2034