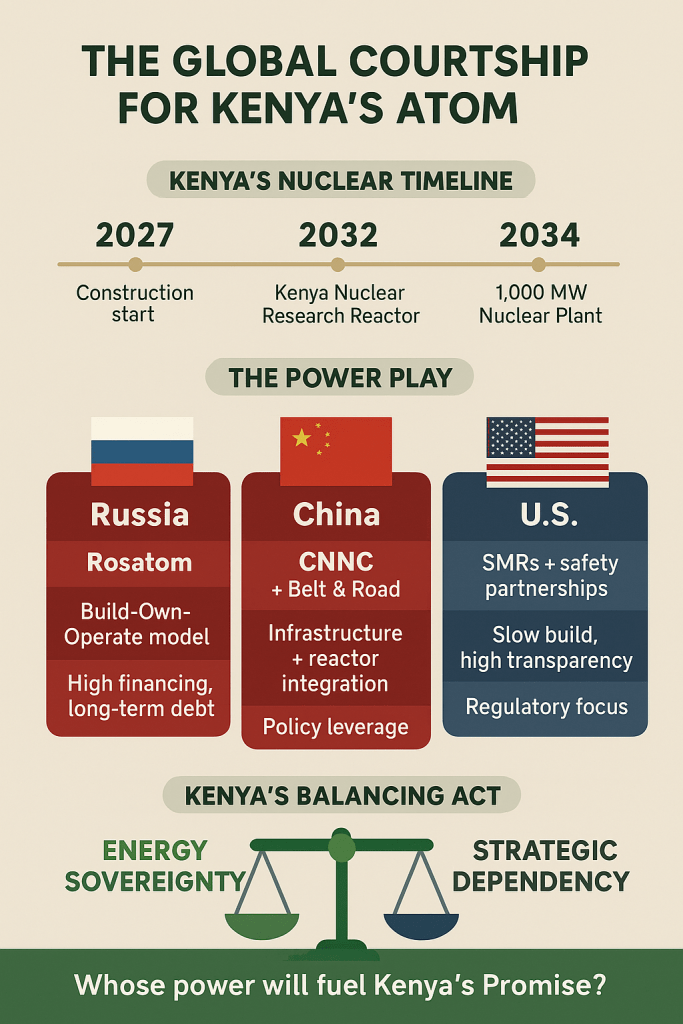

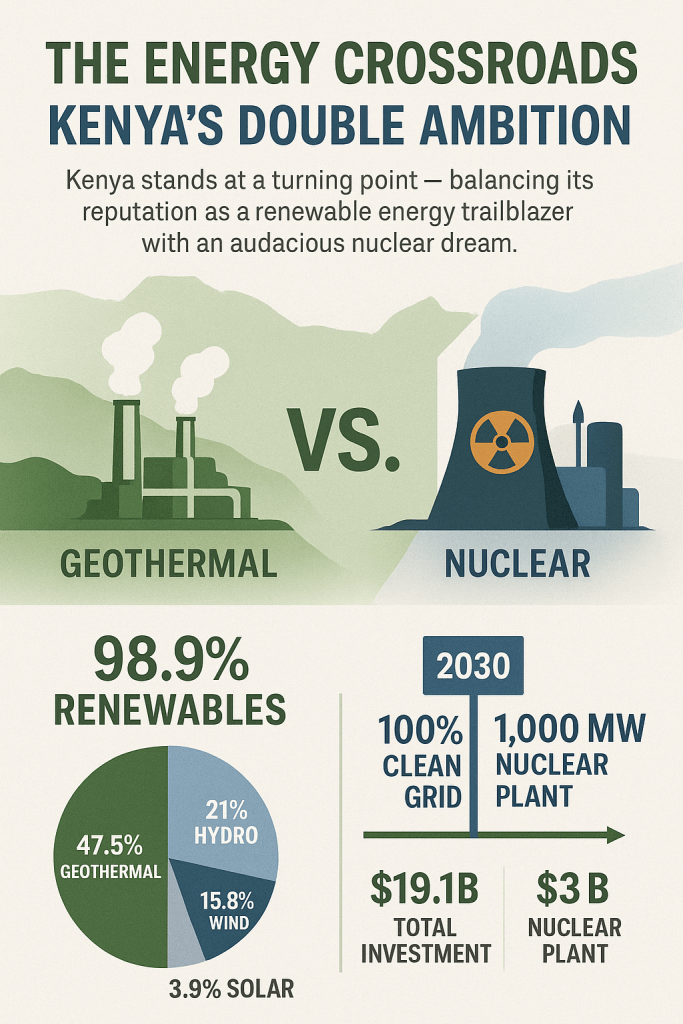

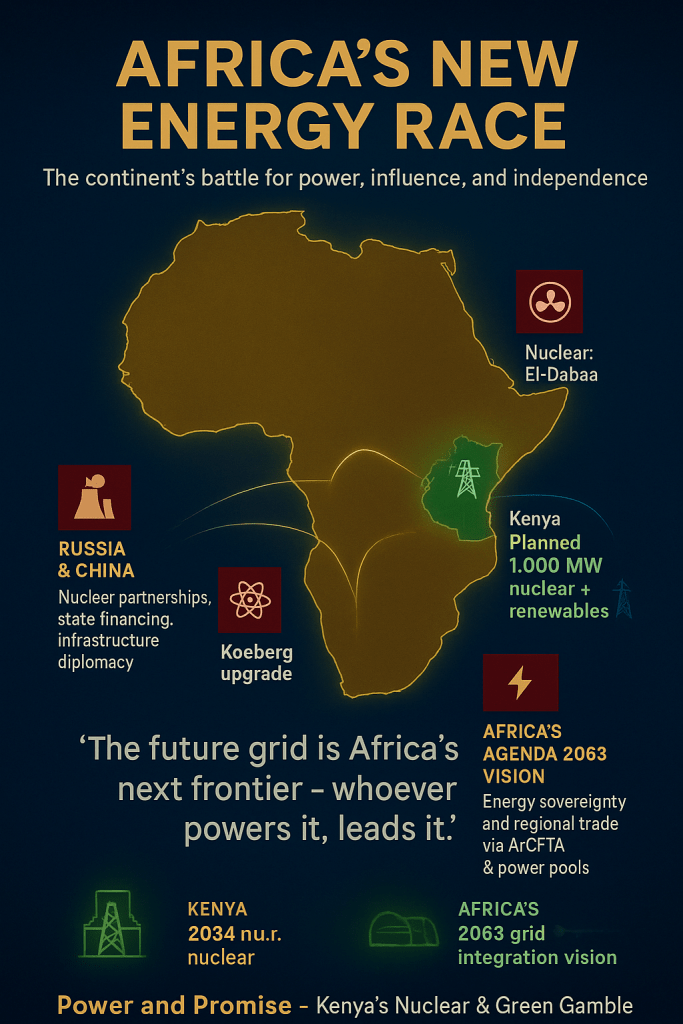

Africa’s energy landscape is shifting faster than at any time in its postcolonial history. From North Africa’s nuclear ventures to Southern Africa’s hydrogen ambitions, the continent is quietly constructing a new map of power — one defined not by oil reserves, but by grid capacity and global alliances. Russia and China are embedding influence through nuclear partnerships; the United States and Europe counter with renewables and clean-tech financing. Across the continent, energy has become the new currency of diplomacy. The story is no longer about light bulbs and power stations — it’s about sovereignty, soft power, and survival. And in this unfolding drama, Kenya stands at the intersection of ambition and caution, armed with geothermal prowess, nuclear dreams, and the burden of fiscal fragility.

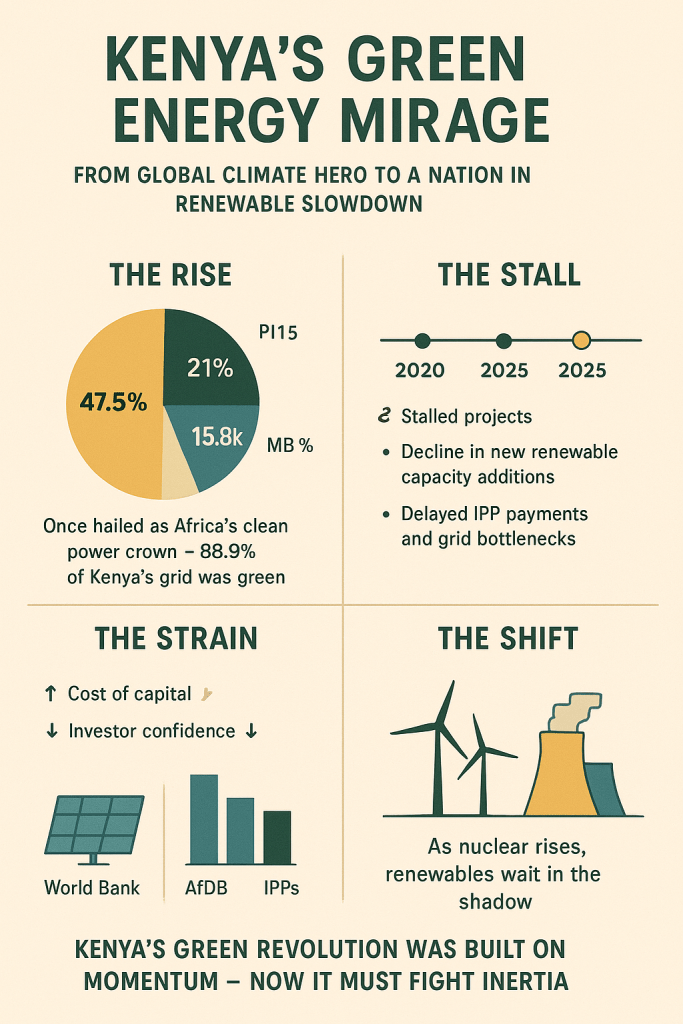

Kenya’s choices now echo far beyond its borders. Once hailed as Africa’s renewable beacon, the nation’s dual pursuit of nuclear energy and grid modernization could redefine East Africa’s energy future — or divide it. Egypt’s El-Dabaa reactor is already nearing completion; South Africa is upgrading its Koeberg plant; and Uganda and Ghana are moving from feasibility to formal partnerships. Kenya, strategically perched in the Eastern Africa Power Pool, holds the potential to become a regional energy exporter, a stabilizer in a volatile market. Yet that promise hinges on policy discipline and trust — two currencies Kenya is struggling to sustain. Its fiscal instability, opaque power contracts, and political indecision risk eroding the credibility needed to lead the continental transition. The dream of an integrated African grid may depend less on megawatts and more on governance — and Kenya’s ability to align vision with viability.

The next decade will determine whether Kenya emerges as a powerful nation or merely a powered one. To lead Africa’s energy race, it must balance ambition with accountability, geopolitics with pragmatism. This is not just about building reactors or expanding wind farms — it’s about mastering the grid as an instrument of economic independence and continental diplomacy. The nuclear plant, if realized, will stand not merely as a symbol of technological progress, but as a test of strategic maturity. For Africa, and Kenya especially, the energy race is no longer about who generates power — it’s about who commands it. The atom, the turbine, and the tariff are now the instruments of influence. Kenya’s gamble could define not just its own future, but the direction of Africa’s entire energy destiny.

References:

Sollay Kenyan Foundation Navigating the Challenges of Kenya’s Energy Crisis in 2025

Semafor Africa’s top bank has a fresh chance to bet on nuclear

Observer Research Foundation Advantage China in Africa’s nuclear energy market race

Intellinews More than 20 African countries exploring potential of nuclear energy – IAEA report

IEA Kenya’s energy sector is making strides toward universal electricity access, clean cooking solutions and renewable energy development

Daily Nation Why Kenya is losing its position as regional energy sector leader