No Bus Fare to the Podium: The Crisis Facing School Sports

The Ministry of Education released the 2026 National Co-Curricular Activities Calendar this week, signaling the return of rugby, athletics, and drama festivals to the school term. On paper, the stage is set for Kenya to groom the next generation of stars ahead of the Glasgow 2026 Commonwealth Games. However, a look at the school bank accounts reveals a disconnect that threatens to cripple Kenya’s sports pipeline. While the Ministry has disbursed capitation—including a “Games Fund” vote head—school heads argue that the money is effectively already spent. With debts from 2025 accumulating and the real value of capitation eroded by inflation, principals are reportedly diverting these “luxury” funds to essentials like electricity and food just to keep schools open.

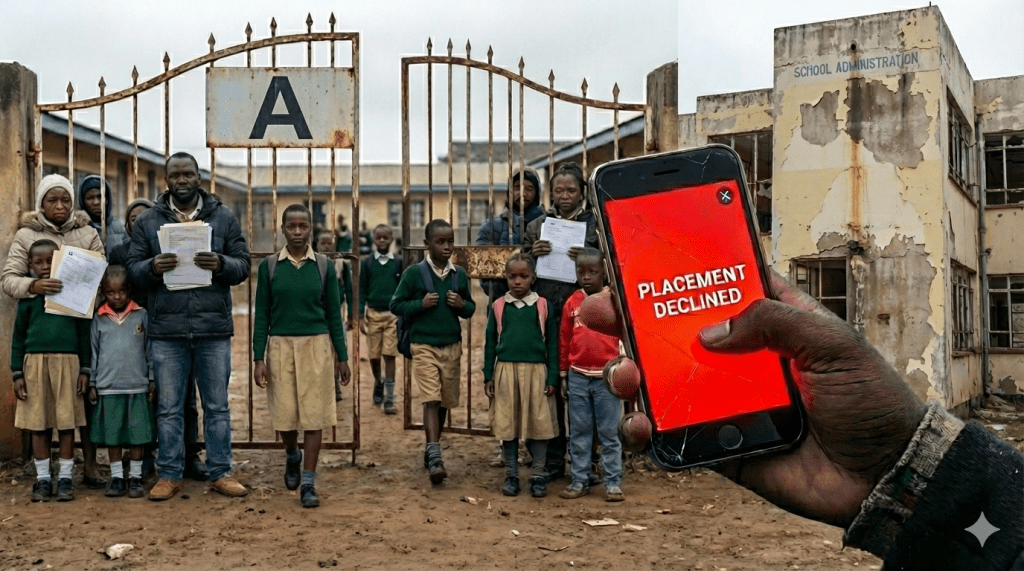

The situation is compounded by the “Strict Compliance” directive that has outlawed the traditional “Bus Levies” and “Motivation Fees” parents used to pay. Previously, if the government funds ran dry, a principal could ask parents for Sh2,000 to fuel the school bus for the Regional Games. That lifeline is now illegal. This creates a scenario where a talented sprinter in a C4 day school in Turkana might qualify for the nationals but fail to attend because the school cannot legally raise the fare. Athletics Kenya has already kickstarted the 2026 season early to prepare for Glasgow, but if the grassroots feeder system—the schools—is paralyzed by austerity, the talent will never reach the national trials.

Furthermore, the National Olympic Committee of Kenya (NOCK) has indicated that its 2026 budget excludes expenses for the Glasgow Games, expecting these to be “funded separately by the government.” This passes the buck back to a Treasury that is already squeezing the Ministry of Education. We are witnessing a high-stakes gamble where the government expects gold-medal results from a system it is actively defunding. As KESSHA Chairman Willy Kuria warns of schools “running on fumes,” it is becoming clear that without a ring-fenced budget for school sports, Kenya’s anthem might be missing from the podium in Scotland.

References:

Scribd NOCK budget excludes Glasgow Games costs

Athletics Kenya AK sets early start for 2026 season to sharpen stars ahead of Commonwealth Games

The Standard Government releases Sh44b in capitation ahead of school reopening

Streamline Public Schools on Brink as Funding Delays Bite

The Kenya Times Nyoro Explains How Schools Got Ksh109 Per Learner as He Questions Capitation

The Kenya Times Ministry of Education Announces 2026 Activities Calendar for Schools Countrywide