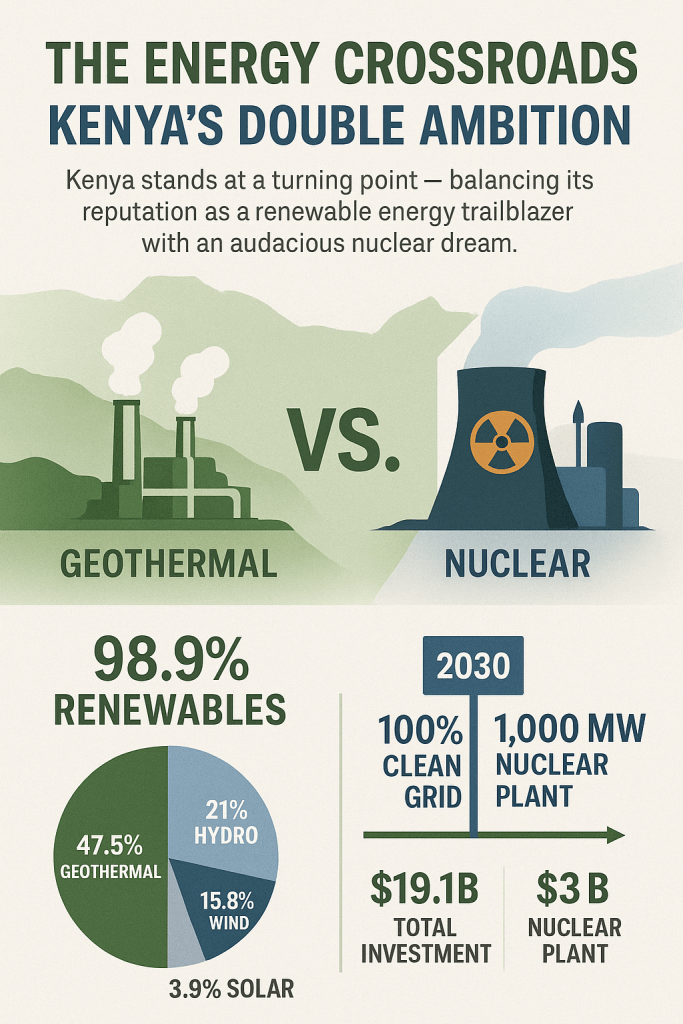

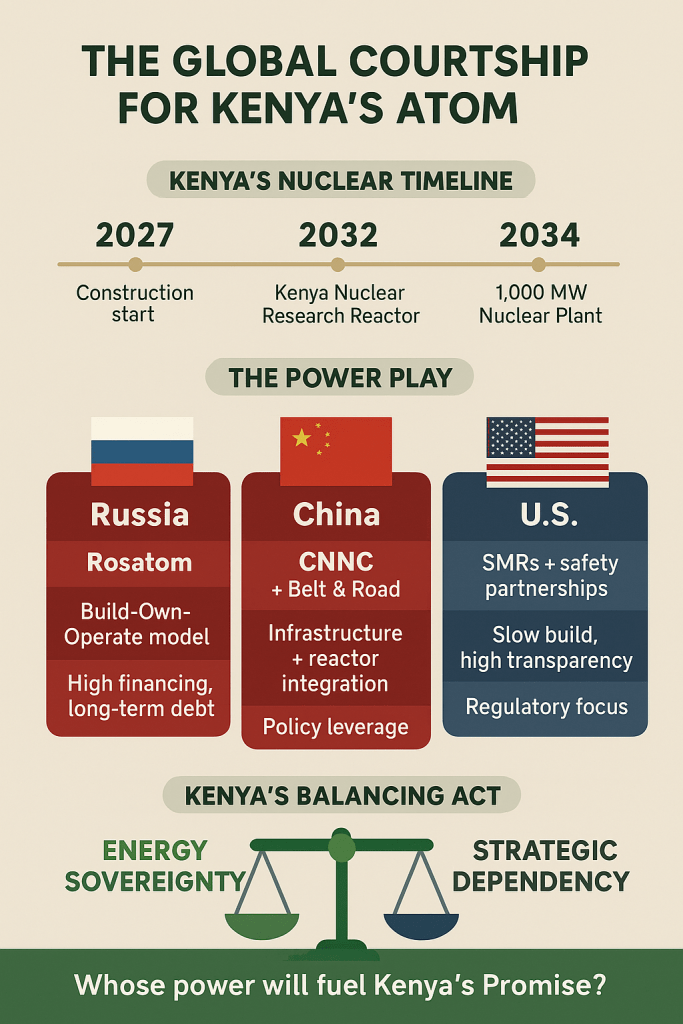

Kenya’s decision to go nuclear has set off more than an energy transition — it has triggered a geopolitical courtship. As the country advances its plan to construct a 1,000-megawatt nuclear power plant by 2034, the world’s top atomic powers are circling. Russia, China, and the United States each see in Kenya more than a client; they see a strategic foothold in East Africa’s next phase of industrialization. Rosatom, Moscow’s state nuclear corporation, has already positioned itself as a leading partner, offering a full-package Build-Own-Operate model similar to the deal it struck in Egypt. China, meanwhile, is extending its Belt and Road footprint to include nuclear cooperation, promising financing, infrastructure, and workforce training. Across the Atlantic, Washington is promoting a more measured engagement — advocating for small modular reactors (SMRs), governance reforms, and safety-first collaboration under IAEA supervision. For Kenya, these competing suitors represent not just technological options, but distinct political and economic futures.

Moscow’s offer is enticing but heavy with precedent. Through Rosatom, Russia promises to finance, construct, and train Kenya’s first generation of nuclear engineers — all while ensuring rapid project delivery. Yet such generosity carries weighty strings. Africa’s only active nuclear project, Egypt’s El-Dabaa, is already testing the sustainability of similar financing terms. The loans are long-term, denominated in hard currency, and backed by state-to-state commitments that can outlast political cycles. For developing economies, such dependency risks trading short-term power security for long-term fiscal vulnerability. China’s playbook differs in form but not in ambition. By bundling nuclear cooperation into its broader Belt and Road matrix, Beijing offers a seamless blend of infrastructure, credit, and control — a model that fuses technology transfer with quiet strategic encroachment. Kenya, already a major recipient of Chinese infrastructure loans, would need to tread carefully to avoid replicating debt traps under a new, atomic banner.

The United States, for its part, sees Kenya as a proving ground for its rebranded nuclear diplomacy in Africa. Washington’s recent “Atoms for Peaceful Growth” initiative seeks to counter Russian and Chinese influence by promoting advanced modular reactors and transparent regulatory partnerships. Its pitch emphasizes capacity-building over construction — slower, perhaps, but anchored in institutional strength and safety culture. For Nairobi, the task is delicate: to navigate between these rival powers without ceding strategic autonomy. Each promise carries peril; each partnership, a price. The nuclear project’s success may depend less on which partner Kenya chooses, and more on whether it can maintain control over the agenda — financing, governance, and public trust alike. For the world’s atomic giants, Kenya is a stage for influence; for Kenya, it is a test of sovereignty. And as this high-stakes energy diplomacy unfolds, the question that follows is equally pressing: can the country’s celebrated green revolution keep pace, or is it being slowly eclipsed by the glow of the atom?

References:

Lida Network Impact of Kenya’s First Nuclear Power Plant Ambitions

IEA How a high cost of capital is holding back energy development in Kenya and Senegal

Nuclear Business Platform Kenya’s Nuclear Energy Sector: A Strategic and Commercial Overview for Investors and Partners

The Africa Report US ramps up nuclear energy for Africa in showdown with Russia, China

IAEA Community at the Heart of Kenya’s Nuclear Energy Debate

The Africa Report Kenya aims to build nuclear power plant by 2034, says minister

Ministry of Energy and Petroleum Kenya signs MOU on Nuclear power collaboration with China

Africa Intelligence Nairobi looks to US rather than Russia for its nuclear programme

Daily Nation Beyond the Cold War: How Russia could help power Kenya’s development agenda

Kenya News Agency Kenya Targets 20,000MW Nuclear Power Plant by 2040

The Star Kenya, China ink major deal to boost nuclear energy development